Vancouver Sun | Politics / Opinion / News

July 4, 2021 | Ian Mulgrew

“Our children are very strong in their culture, they’re interested in their language, their family history, the cultural events.” — Peter Stone

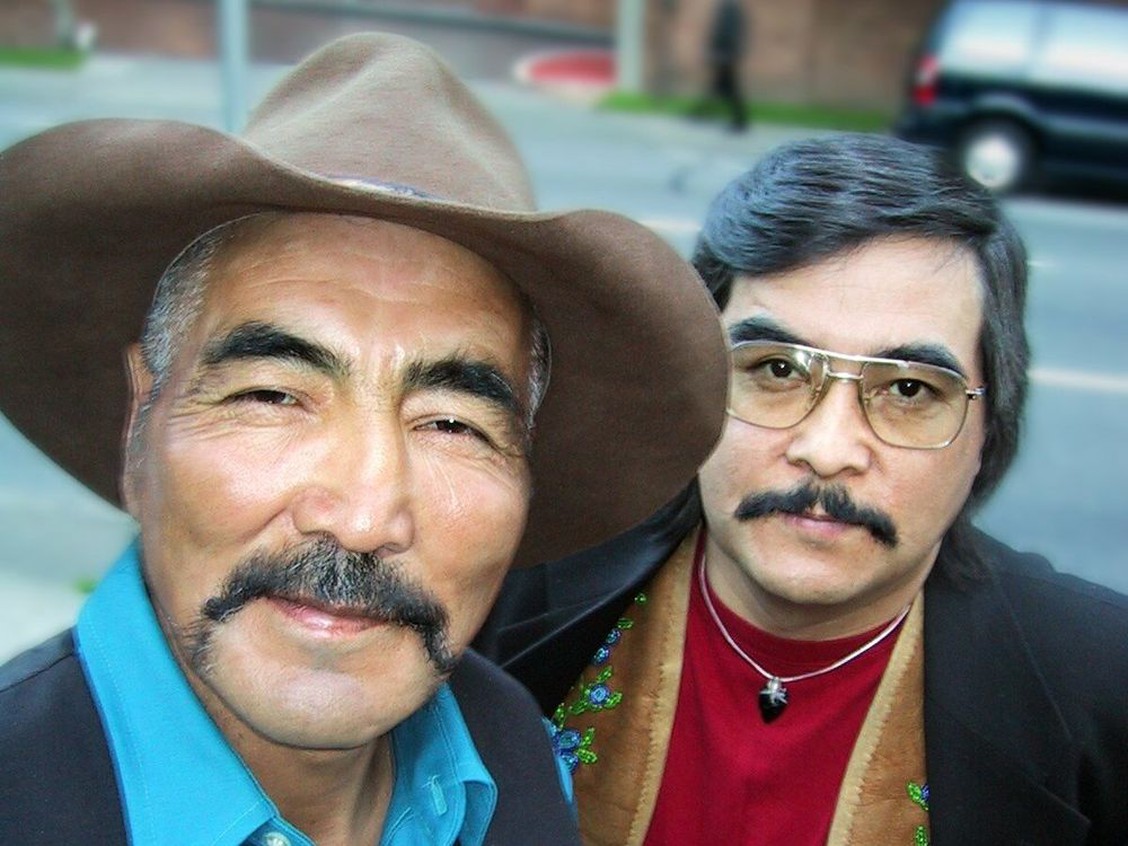

Peter Stone (right) with his cousin George McDonald when they were making the movie Heaven’s Pass, a documentary about the Teh Wa Dena, or People of Stone Mountain. Photo by Malcolm Parry / Vancouver Sun

Peter Stone and I huddled in a poorly constructed cabin in the tiny remote community of Lower Post on the Liard River just south of the Yukon border — it was well below -15 outside and although the stove was working ceaselessly the chinks in the logs quickly exhaled the warmth.

“My legs are dead,” Old Dan Lutz told us between plugs of chewing tobacco.

The federal government assigned him 1901 as the year of his birth, but he claimed to be older.

In a voice filtered through tobacco juice and laughter, Lutz recited his first encounter with a white man.

“I thought it was a ghost with whiskers riding a moose.”

His face and hands were lined reminders of the old Indigenous nomadic life of hunting, fishing, trapping and crafts.

”Old Dan remembers. He knows what it was like,” nodded Stone, then the 26-year-old president of the Kaska Dena Council.

Nearly 40 years later, now a senior himself, he was on the phone from Lower Post recalling the scene: “His family still cherishes that article and the picture in it. … Dan was a traditional chief in our culture.”

In 1984, Stone launched the First Nation’s claim over a huge swath of northeastern B.C. It remains unsettled.

The Alaska Highway had bisected their hunting and trapping area and development all but wiped out the game. The town consisted of clusters of dilapidated log cabins, decrepit buildings that once housed the residential school, the shell of the old log jail, unemployment, welfare and despair.

The Indigenous language was vanishing; only a few understood it and few spoke it. The crafts of fashioning mooseskin boats, moccasins and toboggans were all but gone.

Today, the Kaska Dena number about 3,500 people in seven communities in B.C. and Yukon — others live across Canada, Stone said, and the First Nation is still alive in spite of the challenges.

The hated school building was razed last week and the grounds blessed in a ceremony to prepare for a new cultural centre — a space for self-government meetings, for social and cultural gatherings, and a place to find peace and healing.

A survivor of the school, Stone thinks the 1970s Red Power movement, the formation of national First Nations organizations that followed and his generation of activists have had a hugely positive effect.

Since Canada’s Constitution was patriated in 1982, he complained the country has not addressed the Indigenous collective as an equal constitutional partner or removed the “colonial chains of control.”

“We do not have equal power. Despite the fact that there are many Indigenous languages, none are recognized as an official language like English or French.”

Over the past four decades, Stone has worked in forest management and harvesting, on the railway, in mining and in oil and gas: “I’ve had my taste of resource industries and developed a bit of an understanding of economics in terms of the lands and resources.”

He also has remained involved in his community’s leadership and can only shake his head at the seemingly interminable struggle to achieve autonomy:

“You know, it’s like the wheels and the gears are stuck in the mud as far as federal politics go in this country. We’re still dealing with them on the same terms today (as in the last century) and we’re not really advancing the way we would have hoped … but, currently, I think there is a brighter light and more hope in terms of the B.C. government and reconciliation efforts.”

Instead of working within the modern treaty system, Stone thinks First Nations should use the U.N. Declaration of Indigenous Rights to replace the Indian Act and achieve Indigenous governance structures and self-determination.

Major changes are still needed, he emphasized.

“But there’s a strength that has been born into the younger generations as a result, especially since the closing of these residential school institutions — the youth have been raised by their families rather than taken away and a foreign system of education forced upon them. To me, there is a striking difference now,” Stone insisted.

“Our children are very strong in their culture, they’re interested in their language, their family history, the cultural events. At times when they can’t be home in the North for the cultural activities, they still follow them on the internet and Facebook and all this modern technology. They’re pretty strong on their cultural identity.”

That’s moving in the right direction, he asserted.

“Although there are larger political ongoing issues and battles, for example, the child welfare system, the youth today I think are reinvigorated just knowing the damage and the rough trails that their families and grandparents may have experienced.

“It’s the resilience and I think that there are a number of things they see in that — the value of family, the value of community, the value of Indigenous culture, the value of being able to make decisions locally, about being able to represent and speak for themselves, their family and community, to be able to do things rather than have some Indian Agent if you will, or provincial official come into the traditional territory and try to tell the people what to do. Those days are gone.”