The following stories, videos, and audio contains material about the harmful legacy of residential schools and may cause trauma. If you need support, please contact the 24-hour Residential School Crisis Line at 1.866.925.4419.

The Globe and Mail | Canada

December 10, 2021 | Lower Post, B.C. | Patrick White

In the 1950s, Kaska Dena children and a lone Mountie tried to bring a sexual predator to trial – but the Catholic Church’s intimidation derailed the case. The search for healing continues.

I. Where they got us

The construction crew soaked the lumber with canola oil, then diesel. One of them handed a propane torch to Fred McMillan, a Lower Post First Nation elder.

“You do the honours.”

Mr. McMillan thrusted the roaring torch into a pile of jagged timbers and stepped back to watch the diesel explode and the old timber sizzle.

The walls and floors that had once confined them, that had absorbed their childhood blood and tears, now erupted in light and smoke, rising out over the rustling Liard River before dissipating into the autumn chill.

Melvin Tibbet kept close, mesmerized by the old basement’s glow. “Right there at the bottom of the stairwell,” he said, the flames reflecting in his glasses as he wiped his eyes. “That’s where the worst of it happened. There was a cot down there. That’s where they got us.”

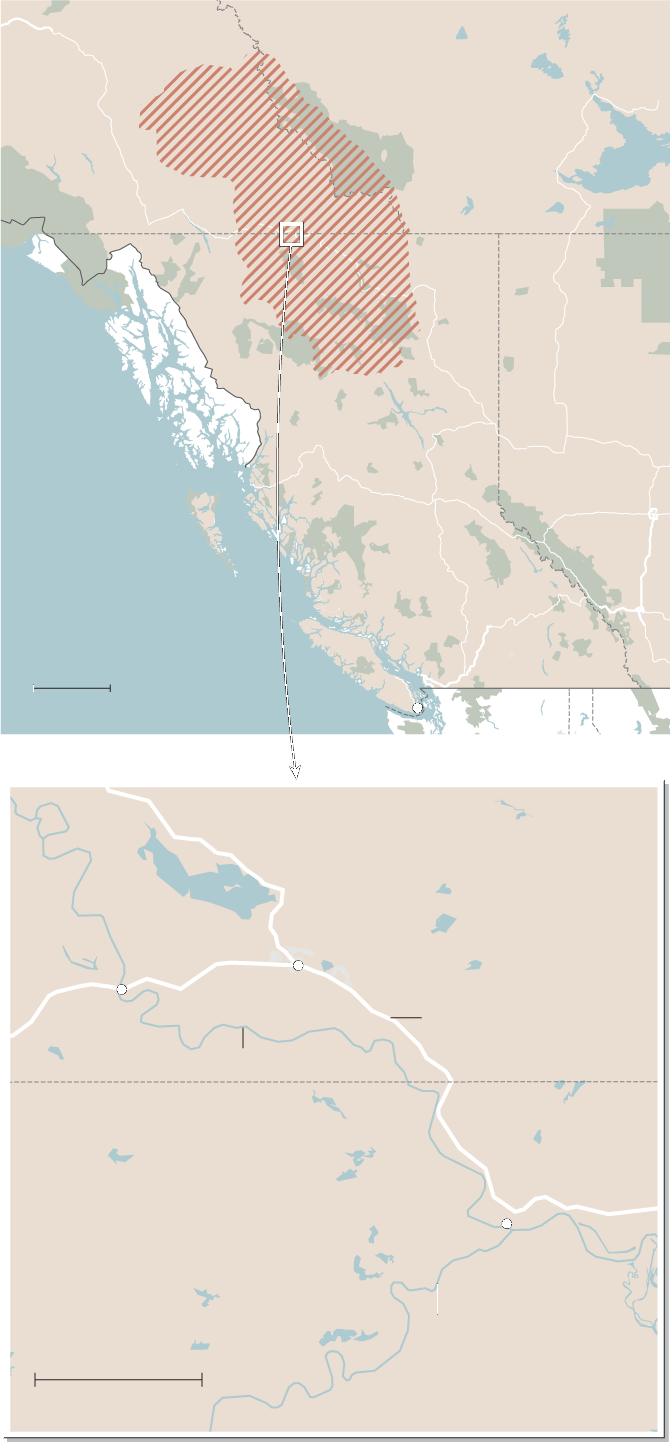

This wall of flame was once Lower Post Indian Residential School, situated a few kilometres south of the B.C.-Yukon border, geographical heart of Dene Kēyeh, lands of the Athabaskan-speaking Kaska Dena people.

Operated by the Catholic Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate from 1951 to 1975, the school was a relative latecomer to the country’s patchwork of Indigenous residential schools that stretched from Vancouver Island to the High Arctic and east to Nova Scotia.

It is impossible to overstate the damage wrought by the Lower Post school in its 24 years of operation, or its 45-year afterlife as a community administration building and post office, providing the 100-person settlement with a constant reminder of the torment that derailed so many lives.

This year, the community’s young chief, Harlan Schilling, had the building demolished, part of a plan to heal old wounds and reverse the cultural erosion that accelerated with the school’s construction. The abuse at Lower Post was sexual and physical – all proven in court during a flurry of police investigations and civil lawsuits in the 1990s and early 2000s that brought the enduring trauma of residential schools to national recognition.

The country should have come to a moment of reckoning far sooner.

More than six decades ago, in 1957, a lone Mountie assigned to the nearby town of Watson Lake, Y.T., along with a few determined students, launched one of the first known efforts to bring a residential school predator to justice.

Their untold story is the story of residential school abuse writ small. Through deceit and intimidation, the Church kept victims silent and empowered a serial sexual abuser. The complicity stretched all the way to Rome, where the worldwide leader of the Oblates referred to the Lower Post abuser as a “poor Brother” in archival correspondence that has only recently come to light. Next year, a delegation of Indigenous leaders is scheduled to travel to Rome seeking a papal apology for abetting residential school tragedies.

Slowly but surely, the arc of this community’s history has bent towards justice, only because the children of Lower Post, and that lone Mountie, would not give up their pursuit.

“That officer and those brave kids, that story should be taught in every school in the country,” said Mr. Tibbet, watching the flames crawl through the basement. “That’s the truth part of this. Everyone should know.”

Murat Yükselir / The Globe and Mail, Source: Tilezen; Openstreetmap Contributors; Native Land Digital

II. The boys in the Plymouth

Corporal Dave Friesen slammed the door of his Chevy RCMP cruiser and crunched through the January snow towards the sprawling white school he’d been investigating for five months. It was 10 a.m. At this latitude, a few kilometres south of the Yukon border, sun had yet to shine on the 50 acres of Liard River floodplain occupied by the Lower Post Residential School.

Over his two years at the nearby Watson Lake detachment, Cpl. Friesen had rarely set foot in the school. A child during World War II, he could still remember classmates calling him a Nazi for his Germanic last name, the taunts ceasing only once he’d earned their respect with his fists. School to him was an unjust place, with its own rules and codes, where a child’s future could depend on a bully’s whim. On the occasion of a particularly grim crash along the winding Alaska Highway or other mass casualty, he’d summon the school’s nuns to the scene, their medical training a scarce commodity in the sparsely populated region. Aside from that, he avoided the place.

Which is why the 30-year-old officer wasn’t looking forward to his scheduled interview with the school’s principal, Father Yvon Levaque. Drunks in Watson Lake, violent husbands in Upper Liard, speed-demons on the Alaska Highway – he could deal with all that, the routine stuff of northern law enforcement where the power balance was clear: He represented order; they represented trouble. But down in Lower Post, in the winter of 1958, people followed different codes and icons. Not so much the badge as the cross. Not so much the threat of jail as the threat of damnation. Cpl. Friesen had come to think of priests as powerful village mayors with eternal mandates.

Evidence of that power lay before him as he tromped past a flagpole and up the school’s front steps. In the 1940s, the federal government delayed, then cancelled, plans to build a residential school in the Tlingit village of Teslin, 200 kilometres southeast of Whitehorse, yielding to pressure from Anglicans and non-Indigenous residents, who said the region needed more schools in Whitehorse than it did rural residential schools. But Bishop John Louis Coudert, the tireless head of the Catholic church’s Whitehorse region, pressured bureaucrats and politicians until Ottawa relented with a $400,000 pledge toward a school in Lower Post.

The level spot at the confluence of the Laird and Dease rivers had long been a Kaska Dena meeting place called Daylu (“a place where we gather to trade”) and, more recently, the site of a Hudson’s Bay Company post. The location placed it in northern B.C., pacifying complaints from Yukon and putting the project closer to the North American railway network.

Bulldozers started clearing the site in 1950. It was a rush job, and looked the part. Architecturally, many of the more than 100 residential schools built across Canada echoed the grandeur of cathedrals. Lower Post school, constructed under the supervision of the Department of National Defence, looked more like temporary military barracks: three storeys, flat-roofed, right angled.

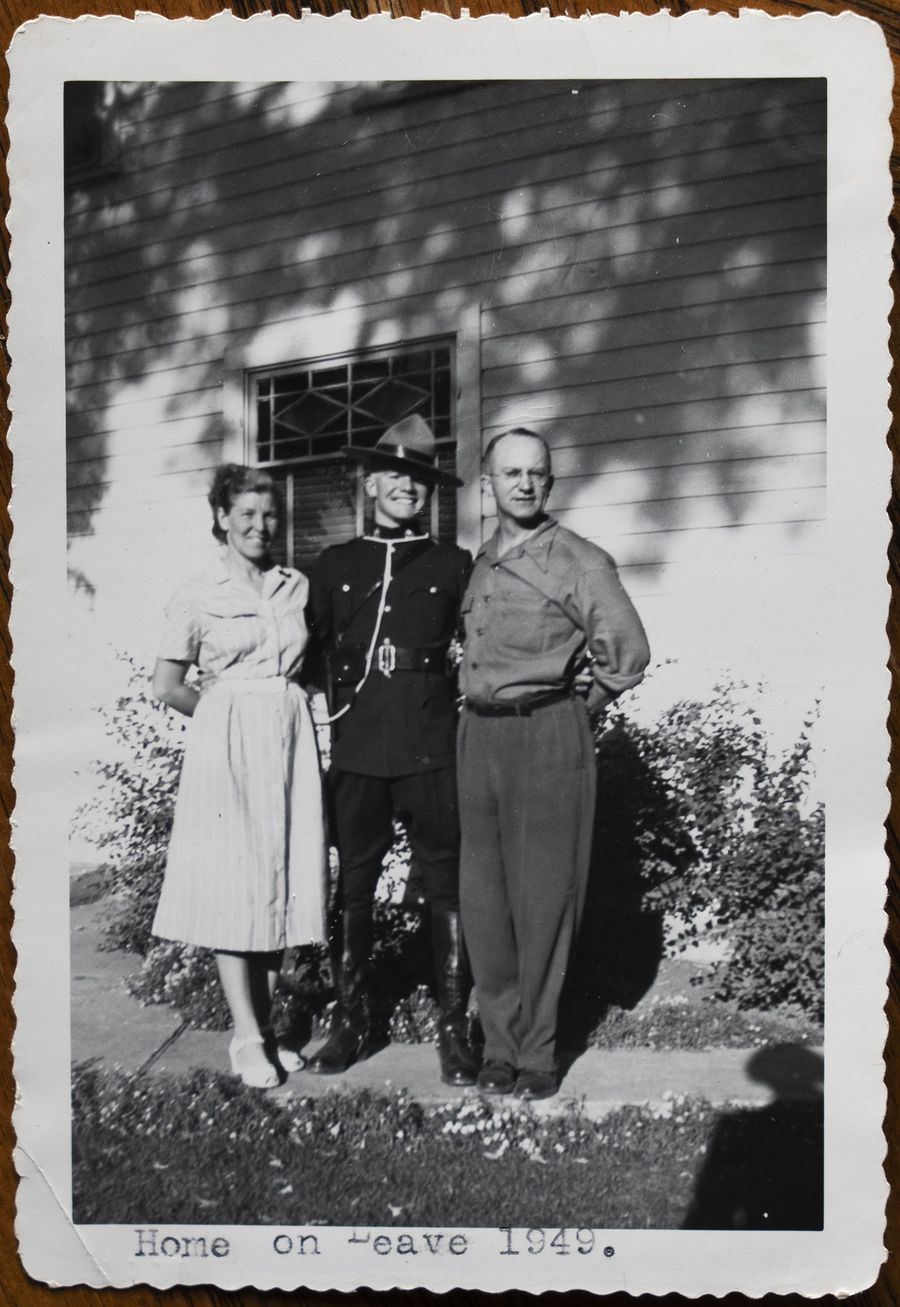

A young Dave Friesen with his parents. Family photo

The residential school building in Lower Post. Photo: BC Government

Inside the school’s front door, Cpl. Friesen noted high-grade Battleship Linoleum floors gleaming under glass ceiling lights. He made his way to the dark-panelled principal’s office. There, he sat down and told Fr. Levaque about his months-long investigation into sexual abuse by one of the school’s former employees.

It had started with rumours. There was a 34-year-old lay-brother at the school named Ben Garand. He drove a hulking Plymouth station wagon, often filled with local kids.

That alone didn’t raise many questions. Hitchhiking was an accepted form of public transit in the area. It was the man’s local nickname that piqued Cpl. Friesen’s suspicions: Backdoor Benny.

In the summer of 1957, the officer had noticed several boys in Mr. Garand’s Plymouth parked outside the Watson Lake liquor store. He kept watch as Mr. Garand got into the car with four bottles of liquor and turned south onto the Alaska Highway, likely bound for his log cabin near the asbestos mining town of Cassiar, across the B.C. border. Transporting alcohol across provincial boundaries was a minor offence, but Cpl. Friesen knew it would give him cause to pay Mr. Garand a visit.

An hour and a half later, he rolled up to the cabin. Inside, he found Mr. Garand, four Indigenous boys, and the four bottles of liquor. He charged Mr. Garand for the booze. The rumours would take further investigation.

In the days that followed, he interviewed each of the boys. They were reticent to talk, except one.

Fate and the Lower Post case brought together Cpl. Friesen and Jack Chief, shown at their homes in Cowley, Alta., and Watson Lake, B.C., respectively. Mr. Chief sits with his wife, Sue.

Photos: Todd Korol & Crystal Schick / Globe and Mail

III. My shock in life

Jack Chief was born in a tent along a family trapline. As he’d later put it, the stars were his lamp, the fire was his stove, the dirt was his linoleum floor.

The Kaska Dena have been called a nomadic people, moving with the seasons inside a traditional territory about the size of Oregon. The land held an abundance of moose, caribou, Dall sheep and whitefish.

Jack had a vague awareness of white settlers growing up. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th-century, the region had experienced sporadic incursion. Trading posts popped up, followed by gold-crazed Klondikers. During Jack’s boyhood, a boat would arrive every spring and traders would ask for beaver hides. Later, his dad would work for RCMP officers stationed at Lower Post. Otherwise, he remained blissfully unaware of the world beyond the family trapline.

But, in 1941, a Japanese bombing raid 4,000 kilometres away would change that way of life forever. U.S. strategists believed Alaska offered Japan its best opportunity for a continental invasion. Sending reinforcements posed a dire logistical problem owing to the lack of any land link between Alaska and the Lower 48.

In just eight months, U.S. Army engineers and thousands of Canadian civilians constructed a bulwark in the form of a 2,700-km road through mountains and muskeg from Dawson Creek, B.C. to Fairbanks, Alaska.

Following the war, the Americans turned the Alaska Highway over to Ottawa for public use. The infrastructure of settler society flowed in: telephone lines, pipelines, building materials. Goods that once took months and years to arrive were now days away. The government encouraged the Kaska to take on more sedentary lives, offering homes and welfare of nine dollars a month per family. Houses, businesses and churches popped up, laying out the promise of a new life, materially and spiritually rich.

In the late 1940s, the Chief family decided to take up the offer. Jack’s mother had died a couple years earlier, leaving him mainly in his grandmother’s care. “We were having a hard time living with my grandma,” he recalled. “When the monthly cheque ran out we’d have to go out and get moose meat or whatever. We were eating a lot of canned bologna, rice and bannock and mush in them days. I still can’t look at bologna.”

Jack Chief smiles at an old photo of his grandmother, Jenny Bob. Photo: Crystal Schick / Globe and Mail

To Jack’s adolescent eyes, the newly built Lower Post residential school offered an opportunity to replace the toil of home life with modern conveniences and new friends. As soon as Jack entered the front doors in September, 1951, he became pupil number 14.

“I was glad to leave home,” he said. “Instead of packing water at 40-below from the river and packing wood from the bush, we had linoleum floors, electric lights, showers. That was all new to me.”

His outlook toward the school soured within a year. The food wasn’t much better than home and all practical lessons took a back seat to religious education. “All they cared about was teaching us religion because they said we didn’t know nothing about God,” he said. “Like hell we didn’t. My grandma always talked about Dena Tee-ah, which means God and good people. Similar concepts, different names. They didn’t teach me a damn thing.”

By the following year, enrolment at the school ballooned from a few dozen to 133, arriving from 40 communities all over Yukon and northern B.C. As one of the original students, Jack saw and heard wave after wave of distraught new arrivals. “These kids would come in there crying, crying, crying,” he said. “They just tore them away from their moms and dads.”

One former student, Mary Caesar, said the abuse began the moment kids walked through the front doors. Upon arrival, their hair was cut and their home clothing taken away. Anyone who resisted was physically reprimanded. “They would punch me in the head and ears,” said Ms. Caesar. “It was just sadistic from the time you stepped in the doors.”

Management of the school was left to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a missionary congregation of the Catholic Church that operated 48 schools across the country, including Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan and Kamloops Indian Residential School in B.C., where, earlier this year, ground-penetrating radar work revealed the presence of unmarked graves. The Oblates recruited upwards of 20 staff. Some lived on site; other maintained homes nearby. For the job of Boys Supervisor, they tapped Ben Garand, who arrived in the North in 1945 as a Lay Brother, a man who has taken the vows of a religious order but is not a member of the priesthood.

From his earliest employment, Garand’s closeness to male students rankled other staff. Survivors today still talk of him as an affable man who offered candy, comics and rides up the highway. Whether driving his own car or a company truck, he usually had at least one local boy riding shotgun.

As Cpl. Friesen would later find out from interviewing more than 30 students, those car trips often led to Mr. Garand’s cabin, where he’d coerce the boys into sharing his bed.

“He gave them rides, he gave them money,” Cpl. Friesen would later say. “And they kept quiet about it because they figured he was a friend of theirs.”

Clergy and altar boys at Marieval Residential School in Saskatchewan, which was run by the same Catholic order as Lower Post. Photo: Société historique de Saint-Boniface/Oblats de Marie-Immaculee du Manitoba

While most of the kids that Cpl. Friesen interviewed spared details about their encounter with Garand, Jack told everything. He wanted it to stop, for Mr. Garand to quit terrorizing him and others.

“I didn’t realize there were people like Garand in the world,” Mr. Chief later said. “I just couldn’t comprehend what he did. Ben Garand was a shock in life, my shock in life. I did not know a man could do things like that.”

Particulars of the abuse needn’t be repeated here. It was pedophilic and soul-destroying. Some Canadians still deny the severity of these assaults. To do so is to ignore voluminous criminal and civil court decisions and years of testimony during Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings held between 2008 and 2015.

Based on Jack’s story, Cpl. Friesen laid a charge of indecent assault against Garand – the first of many to come.

Shoes and children’s toys are left on the steps of the former Vancouver Art Gallery North Plaza on Sept. 30, the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, as communities across Canada honoured lost children and survivors of residential schools. Photo: Amy Romer/Reuters

IV. Cowardly behaviour

As Cpl. Friesen laid out the story of Jack Chief during that January meeting with Fr. Levaque, he expected to elicit shock and concern. Instead, the principal sat stone-faced. When Cpl. Friesen had completed his summary, Fr. Levaque looked at the Mountie from behind his wide wood desk and said that the school was well aware of Mr. Garand’s behaviour. He’d been fired. As far as Fr. Levaque knew, Mr. Garand now drove for a local trucking outfit and was no longer the school’s responsibility. How his students were ending up in Mr. Garand’s car was not his concern. The matter, he said, was closed.

“Why didn’t you report him to the police?” Cpl. Friesen demanded.

“I wanted to protect the church and the school,” said Fr. Levaque, according to Cpl. Friesen’s recollection.

Cpl. Friesen stood and stormed out. From that day on, virtually any time he found Mr. Garand circulating in the community on bail, he’d lay another count of indecent assault against him.

What he took to be his sworn duties turned out to be an anomaly in the history of the RCMP and Canada’s residential school system. In 2011, an RCMP report on the force’s involvement in the schools would make specific note of Cpl. Friesen’s one-man crusade. Based on interviews and archival searches, the researchers found little evidence the RCMP had investigated any community allegations of abuse at a residential school until the 1980s – with a single exception: Cpl. Friesen at Lower Post.

The same report excused the RCMP for its apparent lack of suspicion, stating churches didn’t allow children to “report their problems to the police or other authority figures” and that the schools were “separate from society,” which prevented abuse from becoming public knowledge.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission later confirmed that church officials often colluded with Indian Affairs bureaucrats to thwart and suppress allegations of assault. A passage in the Commission’s final report tells of how the B.C. Provincial Police (the RCMP took over provincial policing in 1950) determined that a group of boys had run away from Kuper Island school because they were being sexually abused. When Indian Affairs caught wind of the investigation, they ensured the abusers fled the province to evade prosecution.

“When it came to taking action on the abuse of Aboriginal children, early on, Indian Affairs and the churches placed their own interests ahead of the children in their care and then covered up that victimization,” the TRC report states. “It was cowardly behaviour.”

Cpl. Frisen had no way of knowing that he was all alone, that of the thousands of Mounties sworn to uphold the law across the country, he may have been the only one investigating sexual abuse at a residential school. Nor could he know the extent of the force’s neglect. By 2015, the claims assessment body set up under the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement had received 38,000 claims of physical and sexual abuse.

“As the numbers demonstrate,” the report states, “the abuse of children was rampant.”

Cpl. Friesen ignored whatever prejudice blinded his colleagues. By late 1958, he’d racked up four charges of indecent assault against Mr. Garand.

A trial was scheduled in Prince Rupert for Dec. 9, 1958.

The Mounties transferred Cpl. Friesen to Edmonton a few months before the child witnesses from Lower Post went west for a trial in Prince Rupert, B.C. Family photo

V. The trial

Cpl. Friesen wanted to keep close tabs on his witnesses in the lead-up to the trial, but in June, 1958, the force transferred him to Edmonton. He didn’t worry. While the bonds of trust between Indigenous people and the RCMP were weak, the boys gave every impression they were bent on justice.

A month before trial, that confidence faltered. As police subpoenaed witnesses, there was one they couldn’t find, Edward Miller. Officers searched every settlement within two hours of Lower Post. A Crown lawyer submitted an affidavit to the court saying he’d been unable to locate the Miller boy.

Jack Chief remembered being locked up ahead of trial to ensure he didn’t flee as well. He couldn’t understand it. Why would the Mounties throw him in jail when they wanted him to take the stand for them? Cpl. Friesen has insisted that the pre-emptive lockup “never happened.”

A Mountie drove the boys 1,200 kilometres south to Prince George, where they met up with Cpl. Friesen for a 12-hour train trip to Prince Rupert.

The rain-soaked port was a bustling city of 10,000 in those days, redolent of fish and pulp mill. The boys had never seen such a place. But at least they ate well. Court pay lists show they received a $6 per diem, plenty to cover three restaurant meals at a time when the local Super-Valu charged 30 cents a pound for hamburger and 25 cents a pint for ice cream.

The first to testify, 17-year-old Leo Sam Miller, trembled as he took the stand to field questions about an assault one year earlier. Crown Counsel Frank Perry, a future B.C. Supreme Court judge, peppered Mr. Miller with a series of questions that elicited some puzzling answers. The teen had already testified before a preliminary hearing, where he’d detailed a sexual assault at Mr. Garand’s cabin. All he had to do was repeat his answers. Something, or someone, was stopping him.

The Crown took on a patronizing tone. To refresh the boy’s memory, Mr. Perry produced transcripts from the preliminary hearing.

“First of all, can you read alright?” he asked the witness.

“Yes, yes I can read,” said the teen.

“Do you understand what I’m doing here?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Do you not understand?”

“Yes, I do.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Well, then, I am just asking you to read it, that is all … Go ahead.”

At this point Justice William Schultz intervened, telling the boy that the transcripts were intended to clear up discrepancies in his testimonies. Once the witness had read the transcripts, Mr. Perry re-launched his examination.

“Going back to December 12th, 1957, you have told us that you came into the cabin at something like 4:30 in the morning,” he said. “What happened after you got into the cabin?”

“I didn’t do anything in the cabin,” said the witness.

“Who did you see in the cabin?”

“Ben Garand.”

“How was he dressed?”

“In his underwear.”

“And when you first went into the cabin what clothing did you have on?”

“Ordinary clothes that I usually wear.”

“Did that stay on or did it come off?”

“No, I took them off.”

“And then what did you do?”

“I went to bed.”

“What bed did you go to?”

“Ben Garand’s bed.”

“And did Ben Garand do anything?”

“No.”

“And after Ben Garand got into bed what was the next thing that happened, if anything?”

“Nothing happened.”

“Nothing happened. I do not think I will pursue it any further.”

When it came time for Jack to testify, he also recanted.

Sitting in the courtroom gallery, Cpl. Friesen felt deflated. All that work. All those kids who’d risked so much to out a sexual predator. All for nothing.

Justice Schultz released a written decision the next day: “Counsel for the Crown, having failed wholly to adduce any evidence of the crime charged … felt compelled to close the case for the Crown without calling further evidence.”

Mr. Garand, the school and the Catholic church were free and clear.

Signs along the highway to Lower Post. The Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate would continue to run the residential school until 1975. Photo: Crystal Schick/The Globe and Mail

VI. Second chances

Cpl. Friesen knew there was more to the retractions. What were they afraid of? Did Fr. Levaque get to them? These questions would torture him on the long trip back to Edmonton. They would remain with him as he and his family bounced between northern detachments – Whitehorse, Coppermine, Yellowknife, Hay River, Fort Smith – until his retirement in 1973 as a Staff Sergeant. And they would persist as he moved to Cowley, Alberta, 90 kilometres west of Lethbridge, settling down on a patch of the foothills he would name Dunmovin Farm.

It was there on the farm, four days before Christmas, 1995, that he opened his Calgary Herald to the headline, “Child-killing claims surface in police probe,” and realized he might get another crack at Mr. Garand.

The story detailed the work of an RCMP investigation he’d never heard of, the B.C. Indian Residential School Task Force. For a year, several officers had been investigating alleged abuses at the province’s defunct residential schools. “So far they have found evidence that 54 people were victims of abuse at the hands of 94 offenders,” the story read. The allegations included at least two accounts of children being beaten to death.

Stories of sexual abuse at residential schools had come to public attention a few years earlier, most prominently in 1990, when Phil Fontaine, then Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, told the CBC’s Barbara Frum that every boy in his grade three class at Fort Alexander residential school in Manitoba had been sexually abused.

The RCMP launched the B.C. task force to deal with the volume of allegations that subsequently came pouring out of communities across the province. To date, B.C. remains the only province to conduct such a thorough criminal examination of all its residential schools.

At age 66, Mr. Friesen saw his second chance at taking down Garand and perhaps solving the lingering mystery of the recanted testimonies.

Three days into the new year, he faxed the RCMP with the story of Lower Post and got a surprising response within hours: the task force had already compiled a thick file on Mr. Garand.

Cst. Paul Richards wrote from the Watson Lake detachment by fax to say that someone from Atlin, B.C., had come forward in 1990 “in regards to indecent acts made against him while attending school there.” As a result, Mr. Garand and George Maczynski, an instructor at Lower Post from 1956 to 1958, had been charged with various sexual offences. Both were scheduled for trial in Terrace, B.C. in December of 1995. Mr. Maczynski got 17 years in prison for 28 counts of indecent assault, gross indecency and other charges.

That was the good news. The fax continued: “Garand, however died of illness complications while incarcerated in Mountain Institution Penitentiary, B.C., this past Fall after being convicted of other sexual charges in B.C. It is worth noting that he was facing other charges in B.C. as well as ours for the residential school at his time of death.” Cst. Richards went on to speculate why the boys had changed their story. “Perhaps the system was not conducive to the boys making disclosure against Garand at that time … I believe you should consider yourself a pioneer, in a sense, attempting to stop the cycle of abuse where it began. The victims simply needed time and distance to conclude the matter.”

After settling in Cowley, Cpl. Friesen would find himself drawn back into the Garand case in the mid-1990s. Photo: Todd Korol/The Globe and Mail

That Mr. Garand died a convict gave Mr. Friesen some satisfaction, but he doubted four decades of delayed justice would provide much satisfaction for anyone involved.

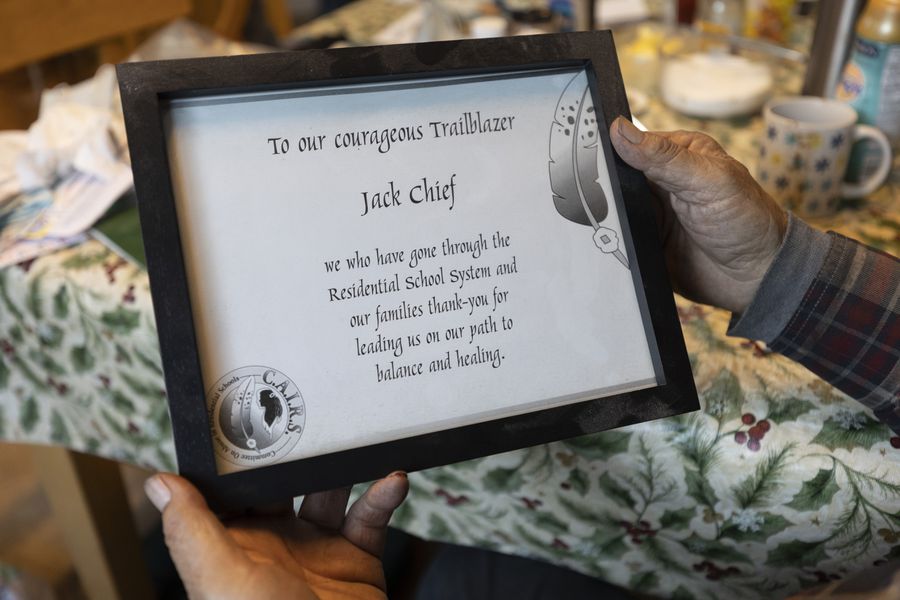

The fax closed one door, but opened another. Cst. Richards mentioned that the victims were suing the federal government and the church. Mr. Friesen got the name of the lawyer on the civil suit, Ron Veale, and sent a note outlining his 40-year-old investigation. His submission proved important to the civil case, in which 12 former students were suing the federal government, the church, Yvon Levaque, Ben Garand and others for abuse they endured in Lower Post school. The group would come to be known around the region as The Trailblazers.

“The Trailblazers are the ones who started everything,” said Mr. Veale, recently retired Chief Justice of the Yukon Supreme Court. “They are the ones who started it, who initiated first the criminal action against Maczynski and Garand in ‘95 and then the court action I was involved with … This was long before the federal residential school settlement came to pass. We were one of the earliest cases.”

Mr. Friesen gave a video deposition. As the case proceeded through the discovery phase, the plaintiffs opted to settle the case for an undisclosed amount.

The names of the The Trailblazers were anonymized and cannot be revealed by law, but Mr. Veale can say that all of them were still suffering from their school experience 30 and 40 years later. “Each one of them had issues, be it alcohol or depression or you name it,” he said. “But the incredible thing was that everybody grew stronger as the process went on.”

In 2001, with more lawsuits mounting, Ottawa created the Office of Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada to resolve the myriad cases in a co-ordinated way. As part of the process, researchers unearthed archival church records to help verify or refute the claims. Among the reams of documents, they found correspondence related to abuse at Lower Post.

Jack Chief holds his Trailblazer recognition plaque, presented to him by the Committee On Abuse In Residential Schools. Photo: Crystal Schick/The Globe and Mail

Neither the Canadian government nor the Oblates would release the full letters to the Globe. An anonymized summary of the correspondence held by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, the archival repository for all documents and testimony related to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, refers to a “Brother” whose dates of employment roughly coincide with Mr. Garand’s and who took up trucking after working at Lower Post, just as Mr. Garand had.

In one letter, dated June 17, 1955, someone with the Vicariate Apostolic of Whitehorse (then under the authority of Bishop Coudert, founder of the Lower Post school) suggests to the Provincial Father in Montreal that the Brother’s behaviour had been flagged before he arrived at school: “I had presumed that at the boarding school of Lower Post, where children are always closely watched over, it would be easier to stop him from abusing anyone, by allowing him at the same time to maintain daily contacts with the children whose company he certainly enjoys. Because of that we never assigned him the duty of watching over the children; but, despite of that, he always has managed to usher some in his room, to bring them along in the trucks, giving all kinds of excuses.”

An August, 1955, letter from the Vicariate Apostolic in Whitehorse to the Provincial Father in Montreal mentions that the Brother had been transferred from Lower Post to a new position in Fort Nelson. Apparently, he lasted one day before returning to the Lower Post area and taking a trucking job. The letter states that the Brother drove into Lower Post the previous day with a student in his truck.

By autumn, the correspondents debate whether Mr. Garand should return to work at the residential school, with one priest in Whitehorse writing, “I believe we should hold our hand out to him” and agreeing with another priest who “seemed to be in favour of a return to Lower Post, but not before September, 1956.”

Finally, on Aug. 14, 1956, the leader, or Superior General, for the Oblates in Rome, who was then Montreal-born Father Léo Deschâtelets, writes to the Vicariate Apostolic of Whitehorse that “with respect to the case of [the] poor Brother … My soul is pained by this kind of business. I never would have believed this of the poor Brother … It’s a psychological case, and there are many others like it. On [sic] would say that the devil blinds the eyes of these poor minks who commit reprehensible mistakes.”

Nowhere in the summarized correspondence do the priests express sympathy for the children.

Mr. Friesen had always known he was challenging the overt power of the Catholic church in his investigation. As he heard about the letters, he realized there was a covert campaign as well.

Cpl. Friesen is now 93 years of age. The Lower Post investigation remains that one haunting case from his career as a Mountie. In the spring, he read and watched everything he could find about the discovery of unmarked graves in a number of Indigenous communities. Again and again, he heard residential school survivors ask why the perpetrators didn’t go to jail, a question he’s been asking himself since 1958. “It’s a crime,” he said. “I just wanted these boys protected. I’m surprised other investigations weren’t going on. At the time I didn’t know. I didn’t know what was going on in the rest of the country.”

He has other niggling questions. How many more lives had Mr. Garand ruined after walking free in Prince Rupert? How many Yvon Levaques had kept quiet about what they knew, each sacrificing future victims to save their own reputation? And whatever became of the boys of Lower Post?

A raven soars over the Chief house in Watson Lake. These days, Mr. Chief, 82, goes out in the bush for food and firewood and spends nights at home with Sue. Photo: Crystal Schick/The Globe and Mail

VII. All I have to say

At the eastern end of the village of Watson Lake, down a potholed road that snakes past the RCMP detachment, sits a plain white bungalow with a new fifth wheel RV parked in the driveway. This is the home of Jack Chief, age 82.

He can answer some of Cpl. Friesen’s lingering queries, but he’d rather not. Though the Mountie was the first white person to take his complaints seriously, Mr. Chief has been left with a negative impression of the RCMP, an attitude shared through much of the Lower Post community. One Kaska term for police translates to “takers of children.”

“Back in those days, they wanted to put all the native people in jail,” Mr. Chief said on a recent morning. “They were lower people. They were not people at all. That’s the way they treated us.”

His first arrest came at age 17 for disturbing the peace. He’d been watching a friend chop down a flagpole and the Mounties threw him behind bars for being a drunk bystander, he said.

Work was scarce in the region, especially for a teenager with no practical skills, aside from a good working knowledge of the Bible. “They never taught us a damn thing in that school,” he said. “I didn’t even know how to harness a horse.”

He began drinking heavily. With the drinking came more encounters with police. He felt like he couldn’t go for a walk without getting stopped and questioned.

“I was always afraid that they were going to pick me up, wherever I was, so I tried as best I could to stay in the bush.”

In all, his jail stints add up to 10 years.

Over the next few decades of his life, he lost all his childhood friends to alcohol, he says. He managed to hang on until 1994, when he quit drinking and met a woman who told him something he’d rarely heard before.

“This white woman told me she loved me,” he remembers. “It took us a while to get together because I had a hard time trusting it.”

Today, he leads a gratifying life, spending many daylight hours in the bush gathering food and firewood and nights home with a wife who adores him. They’ve towed the RV on countless trips to Vancouver Island to see family.

He’s hesitant to revisit the past, especially where it intersects with Mr. Garand and the 1958 trial.

During one recent conversation, however, he offered up a clue to solving the mystery of the recanted testimonies. Shortly before the trial, he received a visit from someone associated with the school.

“Don’t say a thing,” the man ordered. “Shut it down. Or somebody else will come around and you’ll get yourself killed.”

“Okay,” said Jack.

“Don’t say a word.”

The man told him that his testimony would bring down the school. At that age, Jack prayed daily. The church was his home. He feared the sting of a priest’s strap far more than the long arm of the law. “My story changed right then,” he recalled. “I denied everything.” When he saw Leo Miller and the other boys on the stand, he knew they must’ve received the same threat.

Who was the man? Mr. Chief knows, but won’t say, even though he’s long dead. “He was from the school,” said Mr. Chief. “That’s all I’ll say.”

When Mr. Friesen heard this explanation last month, he let out a long sigh, his long-held suspicions confirmed. He speculated that the unidentified school enforcer may have been Mr. Maczynski, the other convicted pedophile working at Lower Post. “The boys never said anything about the other fellow,” said Cpl. Frisen. “It could have been him. He would have reason to keep this under wraps.”

Harlan Schilling, shown in Watson Lake, believes it’s possible for communities like Lower Post to stop the traumas of residential schools from being passed down through generations. Photo: Crystal Schick/The Globe and Mail

VIII. Helping People Building

When Chief Harlan Schilling was growing up, his mom never mentioned residential school. She was a tea-totaller fiercely devoted to the success of her children. But once her youngest child left home, she began drinking and talking of childhood trauma. The change in demeanour alarmed Mr. Schilling, her eldest son, who confronted her. “I’ve done my job,” she told him. “I made sure the cycle stopped.”

He didn’t necessarily agree with her approach, but he understood it. Today, he considers himself living proof that the chain of intergenerational trauma stemming from residential schools can be broken. Now he wants to bring a similar approach to the rest of the community. It’s the philosophy underlying the Lower Post school demolition and burning, as well as the agenda he’s planned for the years ahead.

Aged 34, Mr. Schilling smiles and bounces from foot to foot when telling stories and emphasizing rhetorical points, his liveliness fuelled, in part, by an ever-present cup of coffee in his hand. Before his election as chief last year, he was a councillor, and before that, an explosives expert with the Canadian Forces. He credits his time in the military for teaching him to navigate bureaucracy.

Convincing bureaucrats to let him burn the school wasn’t easy, he said. Officials continually assured him the building was a safe and viable administration building. About two years ago, the old school developed a sewage backup in the basement. When Indigenous Affairs Canada bureaucrats came to visit that year, Mr. Shilling made sure to hold a meeting in the basement. When it came time for lunch, the officials insisted on going upstairs. “I told them, ‘You expect my people to work in here every day, and yet you can’t even eat lunch down there?’”

The strategy worked. Talks about replacing the building started, and accelerated when a few days of heavy rain hit the region, bursting a pipe in the former school. Mould blossomed across the walls, forcing Mr. Schilling to put staff in ATCO trailers. Last April, Ottawa committed $11.5-million for a replacement facility. It will include a gym, garden and program rooms for storytelling, beading and elders’ tea.

An artist’s rendering of the new building planned on the residential-school site. Photo: B.C. government

Mr. Schilling has greater ambitions. On a fall day, with the poplar leaves ablaze in golds and auburns, he drove his Honda CR-V about 15 kilometres south on the Alaska Highway, stopping at an abandoned motel. He walked past some decommissioned gas pumps and stood in front of a two storey-building with a gambrel roof. The fading sign out front read Iron Creek Lodge.

“This is it,” he said, shifting from foot to foot, coffee in hand. “This is a place where we can break the cycle.” He’s applying for funding to buy the lodge and the 38-acre lot to erect a cultural revitalization centre. He imagines language classes, drug and alcohol detox, fishing and hunting – all towards a goal of propping up teachings that were eradicated when the residential school was built.

Driving back home, he returned to a less optimistic reality. The previous day was Canada’s first reconciliation day and newscasts showed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau walking the beaches of Tofino rather than attending a ceremony. The images hit Mr. Schilling and other Indigenous leaders in the area hard, feeding a sense that this iteration of the Crown isn’t as dedicated to the cause as advertised. Mr. Schilling said his disappointment in the Prime Minister has grown since mailing a piece of the old Lower Post school and some child-sized moccasins to the Prime Minister a few months prior without any response.

Despite the snub, he remains devoted to respectful relationships with all levels of government. Recently, he’s started mentioning Cpl. Friesen’s story to rooms of chiefs and bureaucrats, citing it as an example of good actors trying to overcome a rotten system. In October, he asked several Lower Post First Nation artists to create name-tags for local Mounties. Following a ceremony, all nine officers posted to Watson Lake started wearing the tags, beaded orange and black in Kaska style. Mr. Schilling asked local elders to come up with a Kaska name for the RCMP detachment that was kinder than “takers of children.” Their suggestion: Dene Tsʼį̄́ʼ Négedī Kǫ́ą, or Helping People Build.

He bumps his Honda along the dirt road running past the old school site. All that remains is charred cinder blocks and smoking embers – a big black hole. “I feel pretty accomplished that I got to be part of tearing down something that represented such a dark history for my people,” he said. “Now comes the important part: what are we going to build in its place?”

Behind the story: More on The Decibel

Patrick White speaks with The Decibel’s Menaka Raman-Wilms about what he learned when reporting for this story.

See also:

Daylu Dena Council – Kaska Dena Council

Gathering Around the Fire – Kaska Dena Council

Healing – Interview with DDC’s Harlan Schilling. CHEK | Our Native Land – Kaska Dena Council

Recent Media on Lower Post’s Former Residential School Demolition & New Multi-Purpose Cultural Centre to Come – Kaska Dena Council

Program for the Lower Post Gathering—Ceremonial Demolition Event, June 30, 2021 – Kaska Dena Council

Lower Post Gathering—Ceremonial Demolition Event Rescheduled for June 30, 2021 – Kaska Dena Council

UPDATE: Postponed Lower Post Gathering – Kaska Dena Council

Lower Post Gathering—Demolition & Groundbreaking Event, June 21, 2021 – Kaska Dena Council

Former Canada, B.C., Daylu Dena Council Partner to Build New Cultural Centre, Demolish Former Residential School. News Release – Kaska Dena Council

Former Residential School in Lower Post Slated for Demolition: Premier. Vancouver Sun – Kaska Dena Council

Old Residential School – Interview with DDC’s Harlan Schilling. CBC Radio | As It Happens – Kaska Dena Council