The Globe and Mail

October 22, 2017 | Justine Hunter

It is now commonplace for social activists to acknowledge they are living upon unceded Indigenous territory in British Columbia. It is a milestone, however, for the premier of the province to adopt that language.

Premier John Horgan is reaching out to business leaders and investors to encourage economic development, but he says reconciliation with Indigenous peoples must be part of any future growth.

“B.C. is unique in Canada because of unceded territory,” Mr. Horgan said in an interview last week. “I think it would be irresponsible not to take immediate steps to try to find a way to get through the morass. … And if we deny it’s a problem, we won’t resolve it.”

That unique status – a province mostly built on territories that were never ceded through treaty, war or surrender by the original inhabitants – goes back more than 150 years. As a result, uncertainty has dogged economic development in the province, while the courts have been increasingly firm that the Crown in B.C. does not have clear title to the land and its resources.

In the rush to establish the colony of British Columbia, governor James Douglas skipped over the stage of negotiating treaties. In 1859, he issued a proclamation that declared all the lands and resources in British Columbia belong to the Crown. At that time, the colony had about 1,000 Europeans and an estimated 30,000 Indigenous people.

It was not until 2014 that the Supreme Court of Canada, in the Tsilhqot’in decision, ruled that Indigenous Canadians still own their ancestral lands unless they signed away their ownership in treaties with government. The province fought the Tsilhqot’in Nation, a small community of 400 people in the remote Nemaiah Valley west of Williams Lake, every inch of the way in the courts, but was finally forced to accept that aboriginal title exists.

Yet, that admission did not clear a path through the morass. B.C. has 203 First Nations today, many with overlapping land claims, and little progress to show from treaty negotiations.

A handful of treaties have been settled, but many more communities have abandoned the process.

But a rare alignment in federal and provincial intent could provide the opportunity that has been missing over the past 158 years to achieve certainty over B.C.’s land base.

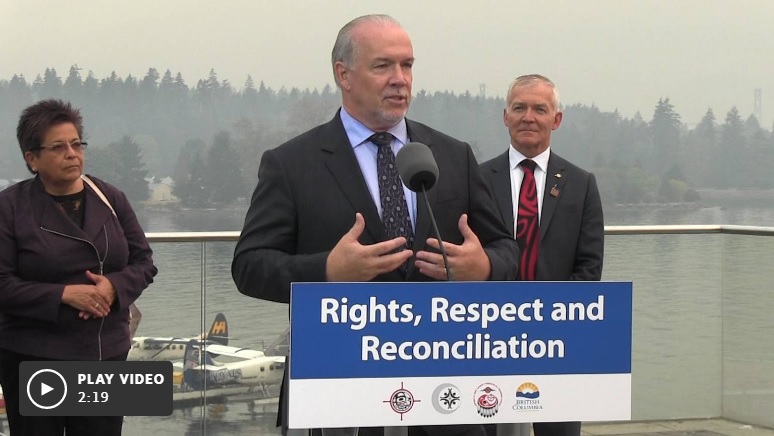

When the B.C. NDP government took power in July, it joined the federal government in a commitment to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It means both levels of government are formally committed to reconciliation and recognition.

Mr. Horgan said the Supreme Court’s ruling in Tsilhqot’in made reconciliation inevitable. It will be delivered by the courts through more litigation if governments do not seek it through negotiation. He said he intends to “intensely” pursue a dialogue that will result in negotiated solutions.

He credited former BC Liberal premier Gordon Campbell with coming close to a breakthrough eight years ago, with the proposed Recognition and Reconciliation Act. In it, the province would have recognized the existence of aboriginal title and rights. But the effort fell apart, opposed by the business community and some First Nations leaders.

“If we can get that close, we can get conclusion,” Mr. Horgan said.

Grand Chief Ed John of the First Nations Summit, the leading advocacy organization for the province’s Indigenous governments, said the Premier’s acknowledgment of unceded territory is significant.

“The word ‘reconciliation’ is partner to those two words, ‘unceded territory,'” he said in an interview on Friday. “The significance of that is the acceptance of the recognition of the rights of our people.”

After years of promises, Indigenous leaders will want more than words. Mr. John helped write UNDRIP, which includes a clause that states Indigenous peoples have the right to redress – restitution or compensation – “for the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used, and which have been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent.”

Mr. Horgan has told Indigenous leaders he does not intend to look back, at retroactive compensation, but he wants to look ahead to shared prosperity.

“We can’t do anything about the lost revenues from the past. But we can look forward and see how we work with industry, with workers, with communities and with Indigenous people to find a way to share the benefits that we all should have been realizing over decades.”

If that is to be enough, Mr. Horgan will need to persuade B.C.’s business leaders not to shy away again, as they did in 2009, when the province was “that close” to achieving reconciliation.