The Narwhal | On The Ground

September 1, 2019 | Sarah Cox

The First Nations that have lived in the north for thousands of years are out to prove that a conservation economy and extractive economy can thrive side by side — but first they need the B.C. government to get on board

- This is part 1 of a two-part series on the Kaska Dena’s proposed Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area and the land guardians working to protect their culture and traditional territory. Read part 2 to meet the Kaska land guardians. [Opens The Narwhal]

On a rain-soaked evening in early August, Kwadacha First Nations chief Donny Van Somer walks from his home in Fort Ware to an airstrip in town and climbs into a plane. Every seat in the Beechcraft 1900 has a window.

He buckles up near the front, on the right, near two of his granddaughters and across the aisle from elder Emil McCook, the long-time former chief. A dozen community members squeeze in. Just after 7 p.m., propeller engines thundering, they are airborne.

Flying north from Fort Ware, an isolated community in northern British Columbia at the terminus of a rough logging road, there’s something different about the landscape below. It becomes clearly visible, through parting cumulus clouds and glinting sun, about half-way into the 50-minute flight up the Rocky Mountain Trench, known locally as the “warm wind valley.”

Unlike flights over most of B.C., Van Somer doesn’t see a single clear-cut. There are no mines, no oil and gas development, no hydro reservoirs, no settlements and not a single road. He could walk for weeks on the land below and not meet a soul in the tapestry of boreal forest, sapphire lakes, rivers and snow-crested mountains that stitch together one of North America’s last intact major landscapes.

“We have an area that’s very pristine and very beautiful, one of the most beautiful places, I think, in the world,” Van Somer, a grandfather of 12, tells The Narwhal.

“We call it the Serengeti of the north. There’s an abundance of wild animals. It’s untouched, no roads, just the ancestral trails that we use for getting back and forth.”

New conservancy would be larger than Vancouver Island

The Kaska Dena call this land Dene Kayeh, which translates as “the people’s country.” The Kaska, a nomadic people who followed the seasonal rounds, producing food, shelter, clothing and medicine from forested landscapes, have occupied this region continuously for at least 4,500 years.

In recent times, they have politely declined to put the proposed Eagle Spirit pipeline through their territory, insisted there be no logging north of Fort Ware, negotiated with a Vancouver company that wants to explore for zinc deposits and declined to use their guide outfitting licence because the area has been over-hunted and needs time to recover.

“Now we’ve decided we don’t want to see much development there,” says Van Somer, who is mustached and wears a leaf-patterned shirt in camouflage colours.

“I think it’s very important for us, being First Nations stewards of the land, to protect a piece of the land we can enjoy in its natural state.”

Van Somer is on his way to the annual assembly of B.C.’s three Kaska Dena nations. Held in Lower Post, a picturesque riverside community of 150 near the Yukon border, the theme of this year’s gathering is “protecting our land.”

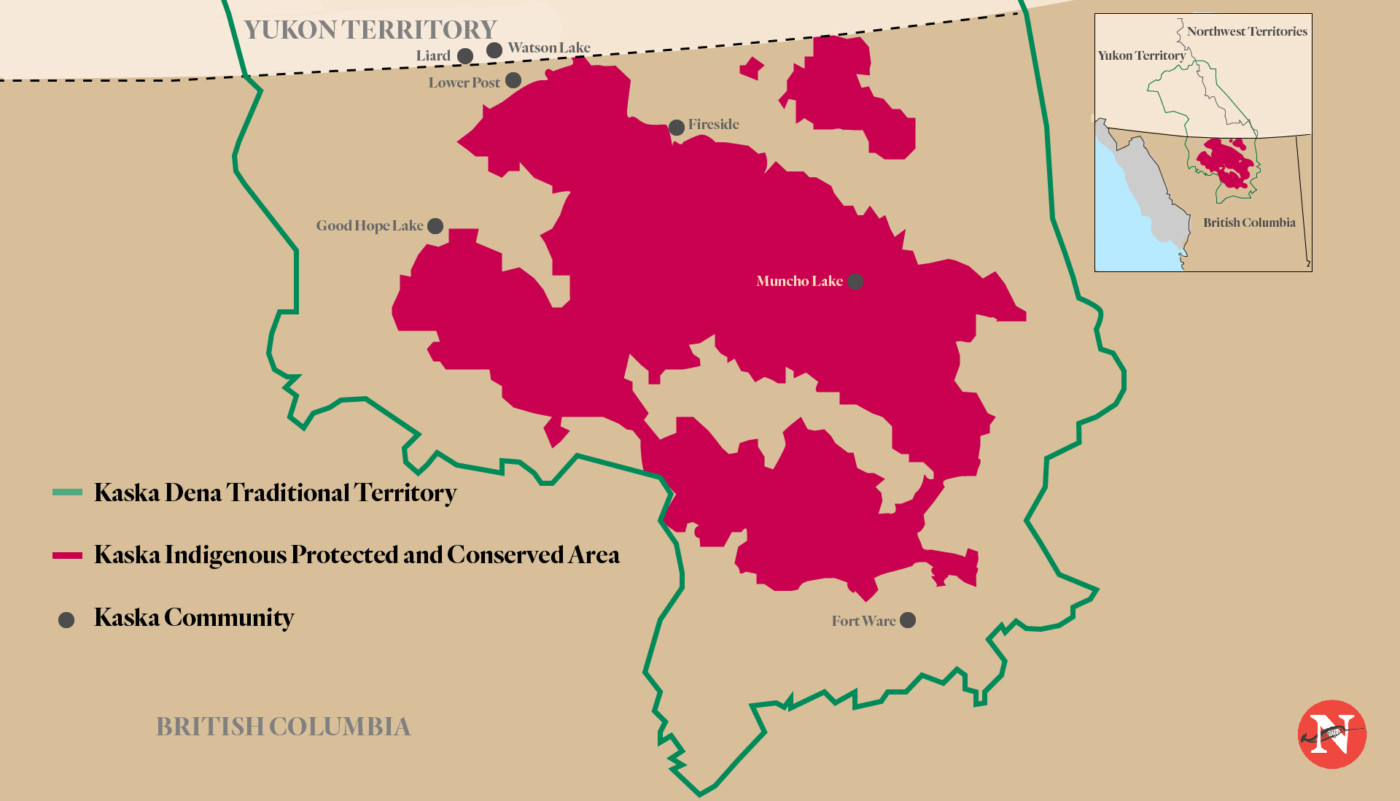

To that end, the topic of much discussion is a proposed Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area that would stretch roughly, tip to tail, from Lower Post to Fort Ware, tilted slightly sideways like a jigsaw puzzle piece.

At 40,000 square kilometres, the new conservancy would be larger than Vancouver Island. You could knit together Jasper, Yoho, Banff and Kootenay parks and still have only about one-half the area the Kaska propose for conservation.

The Kaska Dena say the plan is necessary to protect nature and preserve their way of life at a time when Indigenous cultures across the globe are threatened with extinction and when, every two weeks, somewhere on the planet, another language winks out.

Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

‘Mother Earth is taking a beating’

The conservancy’s first priority, according to the Kaska’s conservation analysis, would be to maintain healthy functioning ecosystems in the boreal forest, a carbon sink known as the northern lungs of the world.

Van Somer points to a report just released by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which highlights a pressing need to restore and preserve forests amidst the worsening climate crisis.

“Mother Earth is taking a beating and there are certain areas that you have to look after,” he says.

As the world’s Sixth Mass Extinction shrinks plant and animal kingdoms, and scientists worldwide warn of a biodiversity crisis and potential ecological collapse, the full suite of wildlife that populated the proposed Kaska conservancy area after the last Ice Age is still found today in relative abundance.

That rich assemblage includes some of B.C.’s healthiest caribou herds, genetically distinct clusters of Stone’s sheep, mountain goats, moose, grizzly bears, orchestras of migratory songbirds, cranes, snowy owls and astonishingly large porcupines that frequent the banks of the Kechika River, known in Kaska as Tahdazeh’, meaning ‘long inclining river.’

A conservation-based economy would create new long-term jobs in land stewardship through an expanded Indigenous land guardians program and ecotourism ventures.

Resource extraction, including logging and mining, would take place on the periphery of the conserved area, while current land uses such as guide outfitting and commercial trapping would be grandfathered in.

“We want to demonstrate how you can have a conservation economy and an extractive economy side by side without losing the values,” says David Crampton, a forest ecologist who works for the Dena Keyeh Institute, a Kaska Dena non-profit agency.

“The fact is, we’re adding jobs in areas where there were never any jobs before.”

Crampton, who previous worked for the B.C. forests ministry in the Nelson and Prince George regions, also has climate change high on his mind.

“With such enormous biodiversity within it, it will protect and act as refugia for a large amount of plants and animals,” he says.

The Kaska Dena vision, announced in June, is quickly gaining political traction. In mid-August, the federal government confirmed it will provide $587,500 to advance the initiative, one of 67 conservation projects supported through the Canada Nature Fund, which aims to expand the country’s connected and protected areas as part of the Trudeau government’s pledge to double the amount of nature Canada protects.

Yet the proposal, backed by a number of organizations, including World Wildlife Fund and the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, can only move forward with provincial government approval.

Next week, on September 10, Van Somer and two other Kaska Dena chiefs will fly to Victoria to meet with three key ministers: Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, Scott Fraser, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, and Environment Minister George Heyman.

“We’re not taking anything away from industry or any other people,” explains Van Somer, who has lived in Fort Ware since he was 10, when his parents returned home from Prince George to run the local store.

“We’re trying to add something for the rest of the world to see. I’m hoping that they’ll listen. I’m hoping that they’ll see our goal.”

‘A very huge impact on the way of life’

Van Somer’s plane skirts Lower Post, veering slightly to the west and crossing the Yukon border to land at the Watson Lake airport. The terminal, with displays of early northern air travel, is deserted.

Half an hour later, travelling along the Alaska Highway in a shuttle bus, the Kwadacha contingent pulls into Lower Post, a traditional gathering place and former Hudson’s Bay post at the confluence of the clear-watered Dease and Liard rivers.

It’s also the site of a former residential school, widely regarded as one of the most abusive institutions in the system, where thousands of children from B.C. and Yukon First Nations were sent and stripped of their identities, including many Kaska Dena children.

Tanya Ball’s mother was sent to the school at the age of six, where she was punished if she spoke Kaska. Today, Ball, a Lower Post resident who runs the Kaska land guardians program, is learning the Kaska names of trees, rivers, weather and wildlife from a traditional knowledge holder who advises the guardians.

“My mum did speak it when she was little,” says Ball, who plans to take a course in Kaska at a Yukon community college.

“My grandma spoke it fluently but she’s passed. After the generation of my parents it was really lost, and of the elders who speak it fluently there’s very few of them left.”

Now the guardians are incorporating Kaska into their land use surveys, so they “will start using the Kaska language and hopefully pass on that knowledge to other people,” Ball explains.

The guardians, who monitor land use, build relationships with hunters and use traditional knowledge and science to keep tabs on everything from wildlife health to water quality, would be integral to the new conservancy.

Kaska traditional territory stretches into today’s Yukon and Northwest Territories, covering about one-tenth of what is now B.C. Decades ago, the federal government artificially separated the Kaska, a self-governing people with their own laws, into four Indian Act bands in three jurisdictions. They’ve lost big pieces of their territory ever since.

In the late 1960s, with no consultation or warning, the W.A.C. Bennett dam on the Peace River inundated an area 15 times the size of the city of Vancouver. It eradicated traditional Kaska trails, meeting spots, burial places, spiritual and cultural sites and the rivers that tied people to family, friends and other communities. The water rose so quickly that some families lost everything they had, including tools like hide scrapers that had been passed down from generation to generation.

“Williston Lake cut off a lot of the river access,” explains Van Somer, whose father was a river freighter and, later, a tugboat captain.

“That was our highway … There was no way to cross that lake. The trails were gone because the trails were all by the waterways. It’s a huge body of water [that had] a very, very huge impact on the way of life.”

With trails and rivers gone, Fort Ware, about 65 kilometres north of the Williston reservoir, was secluded from the rest of the world until a logging road arrived in the community in the late 1970s.

Today the unpaved road remains the only land access to the community of close to 400 people, which Van Somer describes as “one of the most picturesque communities in North America.” To get to the general assembly, Kwadacha elders who don’t want to fly travel along the logging road for 10 hours in the nation’s distinctive white bus, the first leg in their three-day journey.

Another flight on the Beech 1900, emblazoned with the Kwadacha crest in a partnership with Caribou Air, brings more Fort Ware residents of every age to the gathering, while Dease River First Nation members drive from Good Hope Lake, two hours to the south.

The general assembly, hosted by a different community each year, is an opportunity to renew friendships and visit with extended family members over meals that include traditional dishes such as moose stew and moose roasts cooked over a campfire, and to discuss pressing matters like the Kaska’s proposed protected area.

“It will never be like back in the day of our ancestors,” says Van Somer, whose mother was born on a trapline south of Fort Ware.

But keeping the cultural and spiritual core of Kaska traditional territory “as pristine as we can” is a top priority for the community, he says, to have “something we can be proud of, something that this generation kept at, without looting it.”

Ancestral trails a key feature of proposed conservancy

Long ago, Van Somer’s relatives used to travel north by foot, along a 300-kilometre trail through the Rocky Mountain Trench known as Atse Dena Tunna, meaning path of the ancient ones. The path, thought to have been one of the great migration corridors southward thousands of years ago, links Lower Post to Fort Ware, and is popularly called the Davie Trail.

The new protected area would revitalize ancestral trails like the Atse Dena Tunna, the centrepiece in a network of trails that criss-cross Kaska traditional territory. Many follow rivers like the Kechika, a silty, 230-kilometre river that begins as a trickle in the Cassiar Mountains, weaving its way through forests of spruce and pine to join the Liard River near the northern boundary of the proposed conservancy.

Plans are already afoot to start clearing at each end of the Davie Trail, meeting in the middle, creating jobs based in Fort Ware and Lower Post.

Anthropologist Gillian Staveley, a Kaska Dena member, describes the Davie Trail as a historic connection among far-flung Kaska communities of the Northern Rockies.

“Coming on the trail from the Finlay River and over Sifton Pass, to the north, the landscape opens up to expose the beautiful and mystic Kechika River Valley — the heart of the Kaska Dena territory in British Columbia,” Staveley tells The Narwhal. “It’s a very special place.”

The Davie trail branches west into the McDame Trail, in the direction of the Stikine watershed and the Tahltan First Nation, with whom the Kaska traded the coveted goat skin pants they stitched for salmon and obsidian from Mount Edziza.

“It’s a well-established trail, it’s not just a little way-finding wildlife trail through the forest,” Staveley says of Atse Dena Tunna. “It was used heavily. Even the Northwest Mounted Police used it at some point.”

The Kaska are also working with a consultant on an ecotourism business plan that would create opportunities for their members, “who are naturally outdoors people anyway,” Van Somer points out. Some will train as outfitters to “show people the land, tour them around, guide them.”

‘One of the last best places on the planet’

Conservation scientist John Weaver calls the region that includes the proposed Kaska conservation area “one of the last best places on the planet.”

“The unrelenting expansion and development of industrial activities impacts more and more areas, so there are fewer and fewer intact areas — especially large intact areas — left,” Weaver says in an interview.

A recent report Weaver authored examines the Greater Muskwa-Kechika area, which the scientist says is no less important ecologically than the renowned Great Bear Rainforest on the north coast, touted by the provincial government as B.C.’s “gift to the world.”

Weaver’s report, for the Canada’s Wildlife Conservation Society, found more than 98 per cent of the Greater Muskwa-Kechika is still intact, “a very rare thing in today’s world,” he notes.

That means predator-prey relationships — such as between wolves and caribou — are largely undisturbed.

As B.C. caribou herds to the south shrink and disappear — with two more herds becoming locally extinct this year — seven caribou herds in the proposed conservancy area are faring much better by comparison.

Without roads and other linear disturbances creating de facto highways for wolves, caribou, which have evolved over millions of years to spread out on vast landscapes, still stand a chance.

Herds in the proposed Kaska protected area have suffered declines but not nearly to the same extent as caribou further to the south, avoiding costly multi-million dollar penning experiments where pregnant caribou cows are captured and fed lichen hand-picked by volunteers while wolves are shot from helicopters.

The Rabbit herd, whose range would be almost entirely preserved in the proposed Kaska conservancy, was estimated at 1,000 animals in 2018. That could be a wildlife spectacle in today’s industrialized B.C., which holds the dubious distinction of having more species vulnerable to extinction than anywhere else in Canada, and no provincial law to protect them.

“Caribou from my perspective are almost sacred,” says Danny Case, a bespectacled former logger who chairs the Kaska Dena Council, a society formed in the early 1980s to promote and protect Kaska Dena Indigenous rights and title.

“They’re wanderers of the land, very much like our people.”

The Kaska conservancy would provide the roadless, unlogged and unmined areas that caribou need, from mountain slopes to valley bottoms. “That’s critical, that’s absolutely critical,” Case says.

It would also provide connectivity to 14 adjacent provincial protected areas, including the Ne’āh’ Conservancy to the west, tucked between the Cassiar Mountains and the Liard Plains, and the Northern Rocky Mountains Park to the east.

The Kaska envision a place where people interested in adventure tourism can see the world as it once was, before the juggernaut of industrial development advanced into the far reaches of the globe.

“It’s critically important to Indigenous peoples, the Kaska in particular, but I think more so to the planet,” says Case, who believes the conservancy would become world-renowned.

Large landscapes will help wildlife adapt to climate change

Weaver, a scientist for almost 50 years, says large intact landscapes like the Kaska proposal offer the best chance for maintaining resilient ecosystems in an age of global warming, heading into “this very uncertain future of climate upheaval.”

The diverse topography in the proposed Kaska protected area, from the snowy Rocky and Cassiar Mountains to the surprisingly warm Kechika River valley, gives plants and animals “options for the future, for moving around and shifting and finding their new habitat conditions,” Weaver says.

“If they can do that in a very connected landscape so much the better.”

Rivers like the Kechika provide climate adaptation ramps, Weaver says, offering “natural pathways that animals will likely follow as they try to get away from the heat and find cooler conditions.”

As the Arctic warms at a rate far faster than the global average, Weaver says some of North America’s most likely refugia for plant and animal species will be found in the B.C. and Yukon mountains.

“From that big scale, the M-K [Muskwa-Kechika] is well-positioned to serve as a refuge.”

The Muskwa-Kechika is named after two of the unfettered rivers that flow through its valleys (in Kaska, Muskwa means bear).

In 1998, the B.C. government designated the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area, an area roughly the size of Nova Scotia, designed to protect key areas while allowing limited resource development in others.

Protected areas — seven in all — cover just over one-quarter of the management area, while the rest is potentially open to resource development. Even an area called a “Special Wildlife Zone” allows potential mineral and oil and gas exploration, Weaver notes.

He says the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area was visionary for its time. But that was before climate change became a global emergency and science showed that existing protected areas are not large enough or connected enough for wide-ranging species, like grizzly bears and caribou, or for the seasonal movements of species, either now or in response to what Weaver calls “climate heating.”

The management area also does not protect the headwaters of rivers that flow through the greater Muskwa-Kechika and the proposed Kaska conservancy, Weaver says.

“Water is so critically important to all of us,” says Case, “and it’s critically important to us as a people.”

“It’s our blood.”

Boundaries designed to minimize potential conflict

According to Crampton, the boundaries of the proposed Kaska protected area have been strategically designed to avoid or minimize potential conflict with extractive industries such as mining, forestry and oil and gas.

There are no active forestry tenures in the proposed protected area, and forestry tenures on its periphery are exclusively Kaska-controlled, he notes.

Three First Nations woodlot licences will provide jobs in sustainable forestry, demonstrating “how you can have a conservation economy and an extractive economy side by side without losing the values,” says Crampton. He was first hired by the Kaska in 1993 to respond to proposed forestry activities around Fort Ware and kept working for them, drawn by their land stewardship ethic.

“We have areas where we can do some work, make some money, in a way that is actually looking after the environment,” Crampton says in a presentation at the outdoor assembly.

“There is an opportunity for work, and there’s also a core area where we can retain the spiritual and cultural integrity of the people.”

Shale gas deposits in the Liard Basin are also outside the proposed protected area, as are active mineral tenures.

Two active mine tenures, in the southern end of the proposed protected area, are a notable exception. The dominant tenure is held by ZincX Resources, a company that provides jobs for Kaska members in operations south of the proposed protected area, and the Kaska are meeting with ZincX executives to “find a negotiated agreement,” Crampton says.

Mining giant Teck Resources holds the second active tenure, for lead-zinc development. Reached by The Narwhal, Teck’s public relations manager Chris Stannell said the company has not yet been contacted by the Kaska Dena about a conservation area “and would be open to discussions about their proposed plans.”

For Case, the area proposed for protection keeps him physically and spiritually alive, helping to maintain connections among Kaska families and community members.

“It’s so critically important for our people in today’s world that we stick together, that we do our best to maintain our ability to grow together, and to take a lot of what’s happened in the past and allow for forgiveness to a degree, to be able to live in a certain amount of peace,” Case says.

“This particular opportunity provides something that has been the largest question for all our people — how are we going to protect our land? How are we going to protect what we hold dear, what our ancestors held dear? It really means a lot.”

Banner image: The silty Kechika River flows into the crystalline Liard River, creating a colourful contrast near the northern boundary of the proposed Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal