The Narwhal | In-Depth

December 9, 2021 | Stephanie Wood

Canada pledged to protect 25 per cent of land and water by 2025, but British Columbia has added only one percentage point in the past decade. Many say Indigenous protected areas are the way forward. Will the province agree?

British Columbia still hasn’t endorsed the federal government’s promise to protect 25 per cent of lands and oceans in Canada by 2025, leading conservationists and First Nations to call on the province to support more Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss.

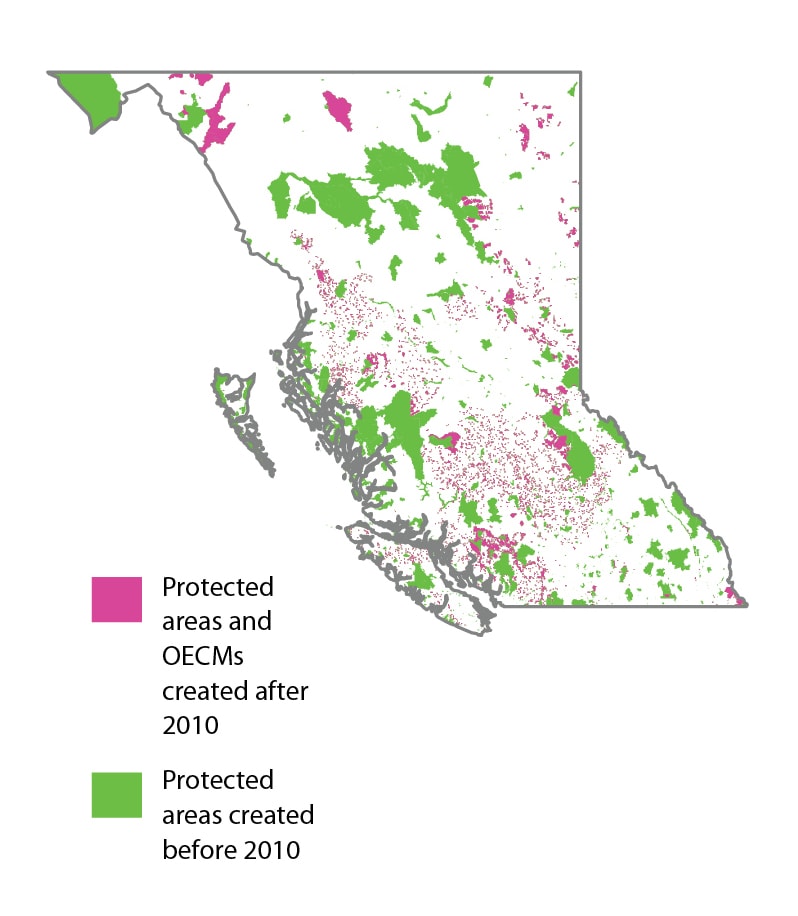

B.C. has protected 15.5 per cent of its land and 3.2 per cent of marine and coastal areas, putting it far ahead of many other provinces and territories. However, it hasn’t established any new large-scale protected areas for a decade, adding just one percentage point over that period through a series of smaller designations.

Hannah Boonstra, spokesperson for the federal ministry of environment and climate change, told The Narwhal in an email that “collaboration with provinces, territories, Indigenous peoples and other partners is critical to protect and conserve Canada’s nature and to recover Canada’s species at risk.”

The federal government has allocated $210 million to develop nature agreements with the provinces and territories “to find alignment” in their conservation goals, she added.

But if there’s disagreement on any issues, provinces and territories “maintain their jurisdictional authority,” she said.

Intact ecosystems are able to sequester carbon, support biodiversity and mitigate climate change impacts like wildfires and floods. Within the next three years, Canada will need to protect an additional 12 per cent of lands and 11 per cent of marine areas to meet its conservation target — and go even further to reach the next level of that goal: 30 per cent protection by 2030.

But that could be a challenge, since Quebec is the only province or territory that has pledged to protect 30 per cent of provincial lands by 2030. This is especially significant in B.C., where over 94 per cent of land is so-called provincial Crown land.

B.C. Crown land is made up of unceded Indigenous territories where Indigenous title was never surrendered and no treaties are in place.

“We don’t see it as Crown land, it’s an area where the Crown claims ownership,” Gillian Staveley, an anthropologist and Kaska Dena citizen, told The Narwhal.

In the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the King of England said land could not be purchased from Indigenous Peoples without first being negotiated in public through the Crown. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that B.C. had no authority to extinguish Indigenous Rights in the 1997 Delgamuukw decision.

Anthropologist Gillian Staveley, a Kaska Dena member, pauses at a waterfall near the Kechika River in the proposed Dene K’éh Kusān Indigenous protected area. The peaceful spot, near a mineral lick that attracts big game, has been frequented by the Kaska Dena people for millennia. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Staveley said Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas are the solution to allowing Indigenous Peoples to uphold their roles as stewards to the land, while enabling the country to meet its 25 per cent goal. Indigenous protected areas are projects identified by Indigenous nations, in which conservation is led by Indigenous governance. She said there is growing “global recognition” Indigenous Peoples are essential to conservation.

She said Indigenous protected areas are also “the most practical application” of the inherent rights laid out in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which B.C. adopted in 2019 to uphold the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Staveley, who is director of culture and land stewardship with the Dena Kayeh Institute, has spent the past few years pushing for the Kaska Dena’s proposed Indigenous protected area called Dene K’éh Kusān in northern B.C. But she said the province has refused to participate. When asked about this, the province responded to The Narwhal that Indigenous protected areas are a federal initiative.

“This is reconciliation with the Kaska,” Staveley said in an interview. “This is what you can do with us.”

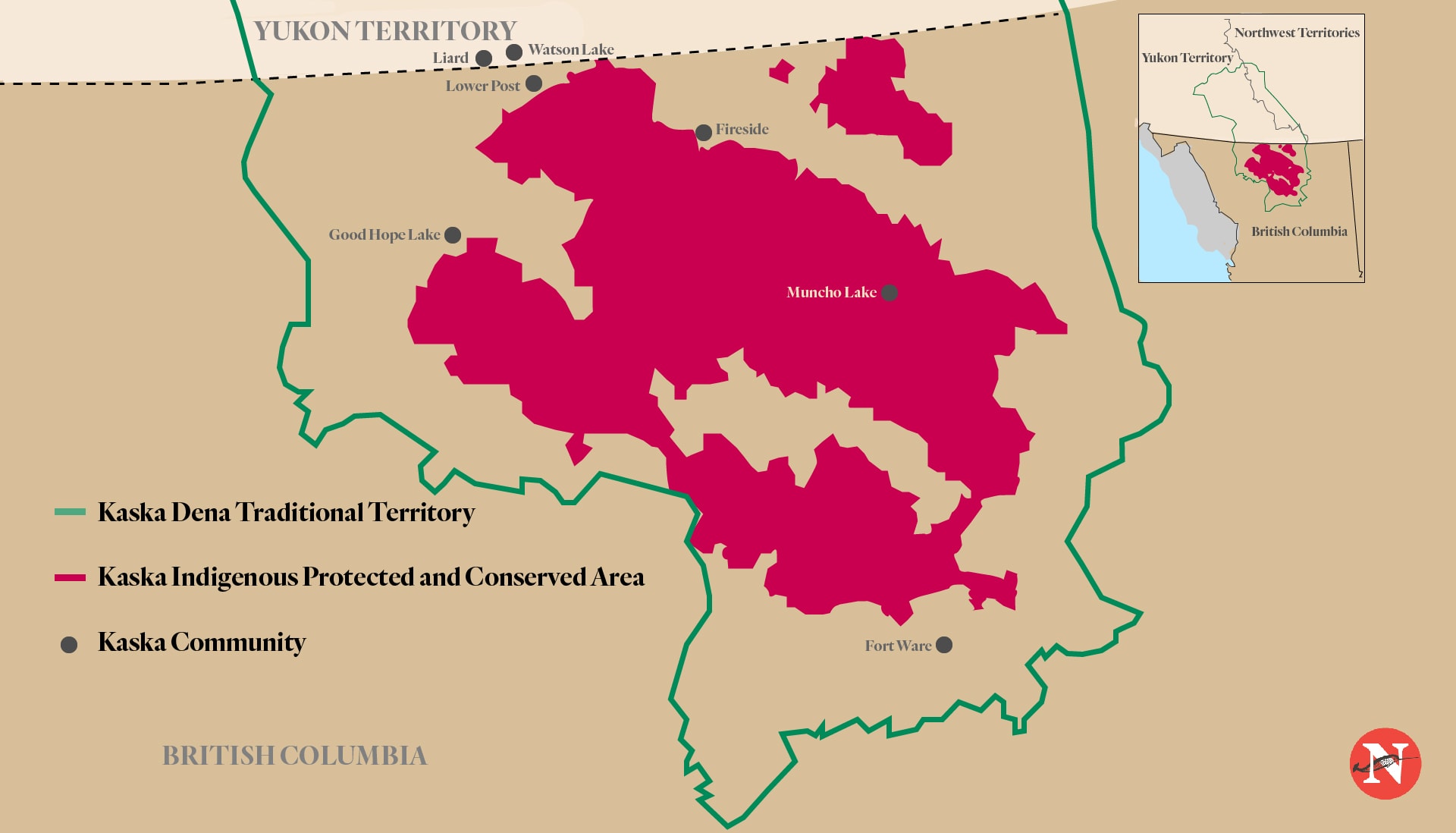

Dene K’éh Kusān (pronounced “deh-nay kay koo-sahn”) means “will always be there.” The proposal would protect 40,000 square kilometres, which is bigger than Vancouver Island. The federal government provided the Kaska Dena with $587,500 in 2019 under the Pathway to Canada Target 1 Challenge, which funds projects that can help Canada meet its 25 by 25 goal.

The proposed boundaries of the Kaska Dena’s Dene K’éh Kusān conservation area. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

B.C. Environment Minister George Heyman told The Narwhal the province has “interest in working with the federal government on how they meet their national targets and how we co-operate with them on that,” but he emphasized it is a federal target.

“That’s a national commitment for the entire country, not each province has to meet it individually,” he said, pointing out the federal and provincial plan to develop a nature agreement in 2022.

“We think B.C. will offer Canada, in many ways, its best chance [to meet its goals] partly because of the amount that we’ve already conserved and partly because of our willingness to work with them on these other measures.”

Staveley emphasized that prioritizing Indigenous protected areas goes much deeper for Indigenous Peoples than just meeting targets.

“Yes, it’s about protecting land, but more importantly it’s about protecting who we are as Dene, protecting our worldview,” she said, adding that it’s not just about percentages but about the areas being conserved “according to Indigenous values.”

B.C. won’t participate in Kaska Dena protected area

If established, Dene K’éh Kusān would bring the province to 19.5 per cent protection. It is still just a small portion of the Kaska Dena’s 240,000 square kilometre territory, which spans across B.C., Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

The 40,000 square kilometres of proposed protected area is on what the province calls Crown land, but which the Kaska Dena call their unceded territory.

The Kaska Dena want to work in partnership with the federal and provincial governments to establish their conservation area, with the aim of having both levels of government acknowledge the protections and restrictions on resource development the nation wants to introduce.

But Staveley says the province has shown again and again it’s not on board.

At least in part due to concerns over conflict with resource development, the B.C. government has not agreed to the Kaska Dena protected area proposal that would cover this stretch of the Kechika River, called Tahdazeh’ in the Kaska language. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

In September 2020 The Narwhal obtained documents written by two assistant deputy ministers about the Kaska plan which said there is “no cabinet mandate or commitment by the B.C. government to continue to add or designate new protected areas.”

A 2019 letter, written after a meeting with Kaska chiefs, described the area proposed for Dene K’éh Kusān as “very important for mining and mineral activities which support both local and provincial economies.”

The documents also said the Kaska proposal would have significant impacts on revenue from forestry in the area, and could also affect mining potential and operations at the Silver Tip mine near the Yukon border. Staveley said this is false because the mine falls about 100 kilometres east of the proposed boundaries. The planned protected area “does not include operable timber land bases,” she added.

Mining claims in B.C. can be staked without Indigenous consent, and critics point out that the province’s Mineral Tenure Act is out of date and doesn’t require companies or individuals to talk to First Nations before staking a claim, let alone obtain their consent.

The Narwhal recently asked the ministry of environment whether its position on designating new protected areas had changed, but the ministry only answered that Heyman “has a mandate to improve access to recreational sites in the province.”

Staveley said correspondence with the province hasn’t changed over the past year since those documents were released.

It’s been tough for her and her colleagues to be told “there isn’t a mandate, there isn’t funding, there isn’t space for this conversation,” she said.

The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act should count as their mandate, she argued.

“It hurts at a very deep level when politicians don’t see it,” she said.

Gwen Bridge, a consultant to Indigenous organizations who is from Saddle Lake Cree Nation in central Alberta, said other First Nations also say the B.C. government is not engaging on conservation proposals.

While the federal government is funding and supporting some Indigenous protected areas, provinces and territories still must participate because Ottawa “won’t expropriate land from the province,” Bridge explained.

She said the federal government could challenge provinces based on its fiduciary duties to Indigenous Peoples established in the constitution, but it hasn’t shown a willingness to do that.

B.C. has supported other Indigenous protected areas, notably the Mount Edziza Conservancy in Tahltan territory established earlier this year, the proposed South-Okanagan Similkameen National Park Reserve in Syilx/Okanagan territory and the proposed Qat’muk protected area in Ktunaxa territory.

A Tla-o-qui-aht proposal for an Indigenous protected area on the west coast of Vancouver Island, where the War in the Woods took place, is in its early stages. Meanwhile, the Gitanyow got tired of waiting for the province to get on board and established the Wilp Wii Litsxw Meziadin Indigenous Protected Area in August, which stands at 54,000 hectares.

B.C.’s protected areas have been stagnant for a decade

In 2015 the federal government, provinces and territories all signed legislation to protect at least 17 per cent of land and inland water and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas by 2020, which was a goal set under the 2010 United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity.

So far no one has reached that goal, but Quebec has gotten the closest, having protected 16.7 per cent of its land, according to a conservation report card written by the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society.

But Heyman argued B.C. is a provincial leader when it comes to conservation, especially if you include “other effective area-based conservation measures” in the total.

“Other effective conservation measures could include things like ensuring that activity is conducted only in certain pockets within a larger geographic area,” Heyman explained. “ Or it could be managing forestry activities in a different way to ensure the natural range of biodiversity ecosystems are protected.”

These areas make up four per cent of the province, so the government will often say it is at 19.5 per cent protection — as opposed to the 15.5 per cent without them. But in its report card the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society found some of these other conservation measures fall short on national and international standards.

Over the past decade, B.C. has stopped short in protecting any large-scale areas, instead designating a smattering of smaller conservation projects or areas of Other Effective Conservation Measures (OECMs) where certain regulations offer a level of protection. Map: Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society

Heyman acknowledged that how the province accounts for these different initiatives is “open to further discussion” and said B.C. has created a team across ministries to look at its reporting methods.

“I think the province thinks we’ve done enough and says, ‘we’ve done more than other provinces,’ ” said Jessie Corey, terrestrial conservation manager at the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society. “They just don’t see the urgency.”

But the majority of the public does seem to see this need. A 2020 poll by Insights West, commissioned by Northern Confluence and BC Mining Law Reform, found 80 per cent of British Columbians would support more protected areas in B.C. created with Indigenous Peoples to meet the 30 per cent protection by 2030 target.

A 2018 poll found Canadians largely believed between 23 and 25 per cent of lands and oceans were already protected — and wanted to see that extended to 50 per cent protection in Canada and globally.

Intact watersheds help mitigate the effects of climate change

Corey said intact forests and watersheds, like that of Dene K’éh Kusān, are essential to maintaining habitat for species at risk. B.C. has 1,807 species at risk of extinction, the highest number among provinces and territories.

In addition, these ecosystems sequester carbon in soil and trees.

“We’re seeing widespread climate change impacts, like flooding and forest fires. This is telling us we need to do more,” Corey said. “That starts with a shift in how we’re approaching land use planning.”

A bald eagle soars through trees in Dene K’éh Kusān, where intact forests offer ecosystem services that advocates argue outweigh any loss of revenue from resource development should the area be protected. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Intact forests and watersheds mitigate flooding by slowing snowmelt and acting like a sponge to water. Logging affects the frequency and magnitude of floods by destabilizing slopes and increasing runoff rather than absorption.

The province is currently facing millions of dollars in infrastructure repairs and land remediation after severe flooding and landslides hit several communities across the lower mainland in November. How much the clean-up will cost remains unknown, but the destructive 2013 floods in Alberta cost around $5 billion in infrastructure repairs. The Fraser Basin Council previously estimated a major Fraser River flood could cause between $20 and $30 billion in economic losses. Further losses are harder to quantify in dollar figures, like how many salmon and salmon nests were impacted by the flooding.

“Our provincial identity is so tied to these images of wilderness and wildlife. This is an opportunity for the province to step in and make those commitments in order to maintain that,” Corey said.

Rather than thinking what money the province may lose by not logging or mining, she said the government needs to shift its focus to “the money we’re going to save through ecosystem services.”

Indigenous protected areas are ‘about sovereignty’

For Indigenous protected areas, “it’s also about sovereignty,” Bridge, the consultant, said.

“Non-Indigenous society needs to shift its understanding to better understand Indigenous laws,” she said. “Conservation is great, but we really need to explore those structural paradigms too.”

She said Indigenous traditional knowledge is often treated as something policy-makers can just “include” in reports or policies, but not recognize as law.

“That’s where the kernel of the conflict is,” she said. “No matter how well-intentioned, if you’re attempting to subjugate the highest level of a society’s law to the lowest tier of authority in western society, that’s not going to work.”

Through creating an Indigenous protected area proposal, Staveley said the Kaska Dena have been documenting and revitalizing laws connected with land management, which centre respect and reciprocity. Like many other nations, they have established an Indigenous Guardians program, employing people to act as stewards on the land.

Photo 1: Kaska land guardians pose by the Liard River in northern B.C. The Kaska have proposed a 40,000-square-kilometre Indigenous protected area. Photos: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal | Photo 2: Jordan, a Kaska land guardian, conducts water sampling along the Kechika River in northern B.C. | Photo 3: Kaska land guardian Robbie Porter uses a tote that held boat equipment to put out a forest fire the guardians spotted near the Kechika River.

“Looking at how guardians are on the land, the types of assessments that they’re doing, the relationships that they’re building — that is our laws in action,” she said.

She sees more opportunities in Dene K’éh Kusān, such as tourism. The Atsi Dena Tunna, or “trail of the ancient ones,” spans from Kwadacha (Fort Ware) to Daylu (Lower Post), connecting Kaska communities and spanning the intact Rocky Mountain Trench valley.

“It goes through the most intact, beautiful wilderness in B.C.,” Staveley said. “But it’s cultured, and that’s what makes it inherently beautiful. Our people still use those areas and celebrate those areas. It’s what connects us all together as Kaska.”

She said the trail passes through where her ancestors came from, and is dotted with places and creeks named after her family. She has dreams of being there.

“There’s a visceral feeling of being connected to a place, that you are one with that place,” she said. “When I’m there, I feel so connected to my ancestors.”

“If other people got to experience that, they’d understand the land better, they’d understand us better. They’d understand Indigenous ways of knowing better. That would be an incredible gift.”

She said she’ll remain committed to Dene K’éh Kusān, and believes it will come to be.

“Our fight will go on forever,” she said.

“It’s our elders’ vision, it’s our ancestors’ vision. That’s power.”

Banner image: Kechika River runs through Dene K’éh Kusān, an area proposed for protection by the Kaska Dena. But the B.C. government isn’t on side and hasn’t designated any large conservation areas in more than a decade. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal